GIANNA VALENTI | Susan Leigh Foster — one of the founders of contemporary Dance Studies, whose books have changed the way we look at dance, the way we think of and write about dance (not only at an academic level) and who has nourished generations of choreographers by providing them with historical perspectives and critical thinking models to define and develop their practices — shares with us her personal process into the making of a dance and of her working on a group choreography.

Foster — dancer, choreographer, scholar at the University of California Los Angeles, internationally renowned writer, founder of the first PhD Program in Dance Studies in the United States, the first invited Professor to give a Research Lecture on Dance in the century-long history of the University of California Academic Senate, honorary member at Laban Center in London, and with a recently awarded Honorary Doctorate from Stockholm University — responded to my invitation by filling her Time Capsule with a narrative that is a flowing example of the function of words in preserving the memory of a creative process and of a choreographic action. A text, at times personal and vulnerable, that offers not only a historical and critical perspective on dance, but also a practical and theoretical opportunity for our contemporary making, as the conscious comprehension of a choreographic process has the power to transform into an artistic dialogue for the definition of choreographic practices in our present.

With deep gratitude, I share with you her words:

At the start of almost every rehearsal in which I am by myself, I crouch head in hands, plastered against the wall, staring out into the space, my body riddled with anxiety. I stay still like this, tense and panic-filled, for many minutes. Eventually, some kind of prompt comes to the surface that seems, if not inspiring, at least viable as a reason to stand and move into the room. Improvising a phrase of movement, I become immediately annoyed by how hard it is to replicate and how dead it appears on repetition. Sometimes I return to crouch at the wall. Sometimes I force myself to stay on my feet and try again differently.

What happens after that? Slowly, and mostly without realizing it, I become immersed in the process of thinking through the next and the next. The beginning of a phrase has potential and the moves start to fall into place. Some dilemmas are solved, at least temporarily, and others get ignored. Prompts build up, turning into sequences; a through-line begins to emerge. I can pause and reflect on it and know which way to go. When this process is at its best, the dance is telling me how to make it. Yes. It takes on beinghood and imprints its future onto me. And it is delightful. «Why not» – I say. «What a good idea». The dance takes some twists and turns, but it knows where it is going. And then it departs. I make some notes and leave the studio for the day.

It almost always returns at some point when I enter the studio the following day. Ideas about the dance that I have when I’m not rehearsing are usually my own, and I bring them to the studio, but the dance always has an opinion. Not only that, the dance is the one who always reveals the ending. There it is, right in front of my eyes.

To be clear, in this process of the dance making itself I am not a vessel or vehicle but instead a collaborator. The dance and I are partnering in its production. But it is also an ego-less collaboration in which there is no sense of a division between will and action. Grammarians have identified this state as that of the middle-voice in which there is no subject or object. A good example of the middle voice can be found in the sentence «Shit happens».

For some pieces what is needed is a sequence of prompts that structure action wherein movement responses remain partially improvised. For other pieces the steps build count by count, building phrases of movement that can be repeated, corrected, and perfected. Each dance requires something different, and often, some different combination of improvised and set material, but the dance making itself remains the same.

I also experience this same sense of collaboration with the dance in performance when I am improvising the choreography. «What does the dance want? What does it need?» – I ask. And it answers. Time shifts out of the metrics attributed to it. It becomes possible to access what has passed and be in the present all at once. Rather than a line, time becomes a volume in which one can move in any direction. I am dancing with and in contrast to what I did earlier in the dance. Some people want to preserve for improvisation the possibility of dwelling only in the moment, only in the present. I prefer to locate the present within a continuity that connects it to all that came before and all that might follow.

Psychologists, including Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, have identified this state as one of special absorption in the act of accomplishing whatever it is – climbing a rock wall, running a race, playing a game of chess or basketball. Calling it a flow state, Csikszentmihalyi argues that it focuses on the merging of action and attention in a way that is non-ordinary and totally absorbing because of its melding of intention and result. Although this merging of person and action is often reported as a loss of self, as Csikszentmihalyi observes, what is lost in flow is not self- awareness, which in fact is often heightened, but instead «the self construct» which «one learns to interpose between stimulus and response».* Thus climbers report a strong increase in their awareness of kinesthetic sensations, just as chess players track the way their minds are reckoning with the game.

While a lot of this sounds similar to what I experience when creating (with) the dance, there’s one difference that may only be quantitative but may also be qualitative. The dance has the capacity to do something really unpredictable and quite outside any ideas I had about it. Are such “crazy but just right” next moves possible in rock-climbing or chess playing or are those activities more circumscribed in terms of the options available? I don’t know the answer to this question, but it may elucidate something about the distinctiveness of art-making… or not.

When I’m rehearsing with a group of dancers, the process is utterly different. I stride into the room, intending to appear confident. I come full of ideas, many more than we will have time to explore in the two or three hour rehearsal period. These proposals for investigations are jotted down on pages I occasionally consult over the course of the rehearsal to make sure I’m not forgetting a crucial piece of what I imagine might be needed for the next phase of developing a dance. I have mapped out a trajectory for the piece, and the purpose of the rehearsal is to move the dancers along that route. Of course, detours occur: the dancers discover a rich vein of movement material that deserves extensive exploration; the dancers scratch their heads in a complete inability to understand what I am asking for; the results of what has been developed signal that the piece is not about what I had been planning.

I go home and draw floor patterns of the scenes developed thus far. Are the dancers moving repeatedly on the same diagonal? Is every scene lasting the same amount of time? Are they all developing at the same pace? Fix that next week!

The drawings of dancers’ trajectories help me rewatch the dance when I’m home sitting on the floor thinking about what follows what. I have in mind a subject matter or rather, an argument, for the dance to develop, and the question becomes how best to develop that argument so that viewers can follow and absorb it. I am not interested in showing only a process of creating action, but rather in communicating a hypothetical world in which people move and relate to one another in specific ways. For this reason I have always believed that choreographing is an act of theorizing. The process explores a set of “what ifs” and then delivers to viewers the provisional answers to those questions. Of course, what viewers see and how they interpret it is an open field of possibilities. But I try over the course of the making of the dance to construct its propositions as clearly as possible. Perhaps the test of this is the number of viewers who arrive at an interpretation of the dance similar to my intentions.

It’s not easy, and often not a good idea, to put oneself in the dance. It’s impossible to see the dance as it is seen by viewers when dancing in it. But often, it is an economic necessity – one dancer I don’t have to pay. So, when I’m building the piece, I identify sections in which I will appear, but seldom rehearse along with the dancers until the performance is about to happen. Then I have to shift gears radically and learn the dance in a whole new way – from within it. This means paying attention to who’s nearby and when, to keeping spatial formations clear, to learning the pacing and its aerobic demands, and projecting my focus out into the space. These are such different skills, although some of the feeling of the dance performing me remains. The dance is delighting in showing itself to an audience, but it is a group effort in which I feel as connected to the other dancers as to the dance.

Are the other dancers also dancing with the dance? Is it dancing them the way it is me? I don’t know. It probably differs for each run-through. I have tried to convey to them what I’m intending (what the dance is hoping to say). But perhaps they (and I?) are more immersed in the ecstasy of our group motion. The now and the next take over the focus of attention.

One other thing happens towards the end of the rehearsals – I get an idea for a new dance. Just as it is finishing up with making itself, the dance presents a new idea for a new iteration of itself. The dance is very clever in keeping itself in action and also considerate of me so that I don’t feel abandoned or uninspired.

All the while that the dance and I are creating it, I am completely entangled in adjacent tasks whose completion is vital to the project: arranging and getting a key for the rehearsal space; renting a space in which to perform; traveling by train into NYC and then to Hoboken where I have rented a bedroom so that I can rehearse twice or three times over a long weekend, all while grading papers and prepping for courses; finding and working with a composer, a lighting designer, and, eventually, a stage manager; designing and printing postcards and posters; writing press releases; scheduling a photographer to take photos of the dance; making or finding costumes and devising props; designing, writing, and printing the program; looking around at what other choreographers were doing and comparing myself with them. Who’s to say that all of this isn’t part of the choreography? Not me.

The choreography continues to unfold: Moving in to the performance space, for tech rehearsals and dress rehearsal, working with all these other people who have such a partial idea of what the piece is about, but cajoling them into understanding and making the right decisions based on their technical knowledge of sound and light boards. They have to bring in and focus the lights; set up the speakers and connect them to however the music is being produced. Someone, usually me, has to set up the chairs and sweep the floor. And when we run the piece, I’m performing in it but need repeatedly to step out to see how it looks and sounds.

And then after three nights of performances, it all needs to be dismantled. Equipment returned, chairs stored away, costumes collected and laundered, props taken home, notes and drawings of the dance filed away along with the photos, advertising materials, and program.

Maybe I take a few weeks off, but the dance has left me with an idea, so I’m eager to start exploring it. I return to the wall in the studio, hunched, baffled… but slowly something emerges.

*****

Mind you, what I have written about the process of making a dance is highly questionable. It’s been many years since I was actively making dances on a regular basis. For sure I remember the crouch at the wall (and I remember smiling ironically at what a necessity it was). I still have the drawings of the floor patterns, so I know I made those. I know very well the feeling of collaborating with the dance and the fantastic surprises it would give me. But this narrative I’ve given makes it seem so clear and contained when I’m quite sure it wasn’t.

Also, what I’ve written describes a nine-year period of time in which, while teaching at Wesleyan University, I was also self-producing in New York City and performing regionally. According to my income tax returns, I was spending half of my annual $34,000 salary on these performances while receiving modest recognition in the form of reviews in the «New York Times» and «Village Voice» and two small grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. This was also a period (the mid 1980s) in which the entire system that presented experimental dance was being overhauled, primarily through the introduction of artistic directors – curators who took over the running of spaces that collectives of artists had previously supervised. These directors claimed for themselves a powerful role in determining who and what kinds of work would be produced. They liked to give advice to the artists they produced. I remember cloaking my disdain (unsuccessfully I’m sure) while listening to their thoughts and suggestions. The Cunningham Studio (where I self-presented) endured as the last well-known space in the city that was rentable on a first come first serve basis. It could hold one hundred people.

Are these infrastructural and institutional conditions relevant to the creative process of dance-making? Interesting question. I’m sure, at least, that they framed the conditions of possibility of what I thought I could create as did the many concerts I attended and the conversations with other artists I had.

*****

In many ways making a dance is not that different from writing this text. I start staring at a blank page just as I stare into the blank room. A little bit gets done every day; some editing and rewriting; some pulling back and looking at the whole and then some zeroing in on a sentence. Words (like movements) are chosen, phrases fleshed out, and sections formed. Eventually arguments are made, one way or the other. The big difference is that with writing there is text to come back to the next day staring back at you from the page or screen, whereas with dance, you have to remember it all and recreate it each day. And then the bigger difference at the end: you have a text that is not permanent, but more permanent, than the dance.

Video, only entering the performing arts in the early 1970s, became a very important tool for choreographers in the 1980s. Providing a powerful and relatively inexpensive way to document a dance, it was also increasingly utilized to record rehearsals so that choreographers had another way, besides their imaginations of reviewing the dance. I never used video in rehearsals, but I’m happy to have the recordings of the concerts.

What are the differences between re-viewing a dance in one’s imagination and on the video, and do these differ from reading what one has written on the page? Video is already a translation from one medium to another, and every choreographer knows that it offers an incomplete accounting of the dance, especially in terms of the kinds of effort experienced by dancer and viewer. It can’t convey the muscularity of dancing, although it may assist in reminding the choreographer of what has been accomplished. But whether I am watching a video or remembering the dance in my imagination, it is a newly creative and interpretative act. It is the dance in this moment.

Isn’t it the same for a text? Isn’t it newly created in each reading? New relationships pop up; a different sense of the words’ rhythm emerges; a newly adjacent idea suggests itself mid-sentence. A time arrives when you’ve said what there is to say.

As I have here.

Susan Leigh Foster

*Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. “A Theoretical Model for Enjoyment.” In The Improvisation Studies Reader: Spontaneous Acts. Edited by Rebecca Caines and Ajay Heble, 150–162. London: Routledge, 2014. p. 36

Credits

Author Susan Leigh Foster

PAC-Paneacquaculture.net

Italian Text

Fare Coreografia #5: Susan Leigh Foster, dancing with the dance

The media link to this text, “Susan Leigh Foster, dancing with the dance”, can be shared with no restrictions. However, in accordance with the Bern Convention on intellectual property rights (copyright), the present text may be quoted, in accordance with proper usage and to the extent necessary to achieve the desired purpose, but it cannot be copied or re-used without the author’s prior approval in both digital and printed publications.

Online references of Susan Foster’s work:

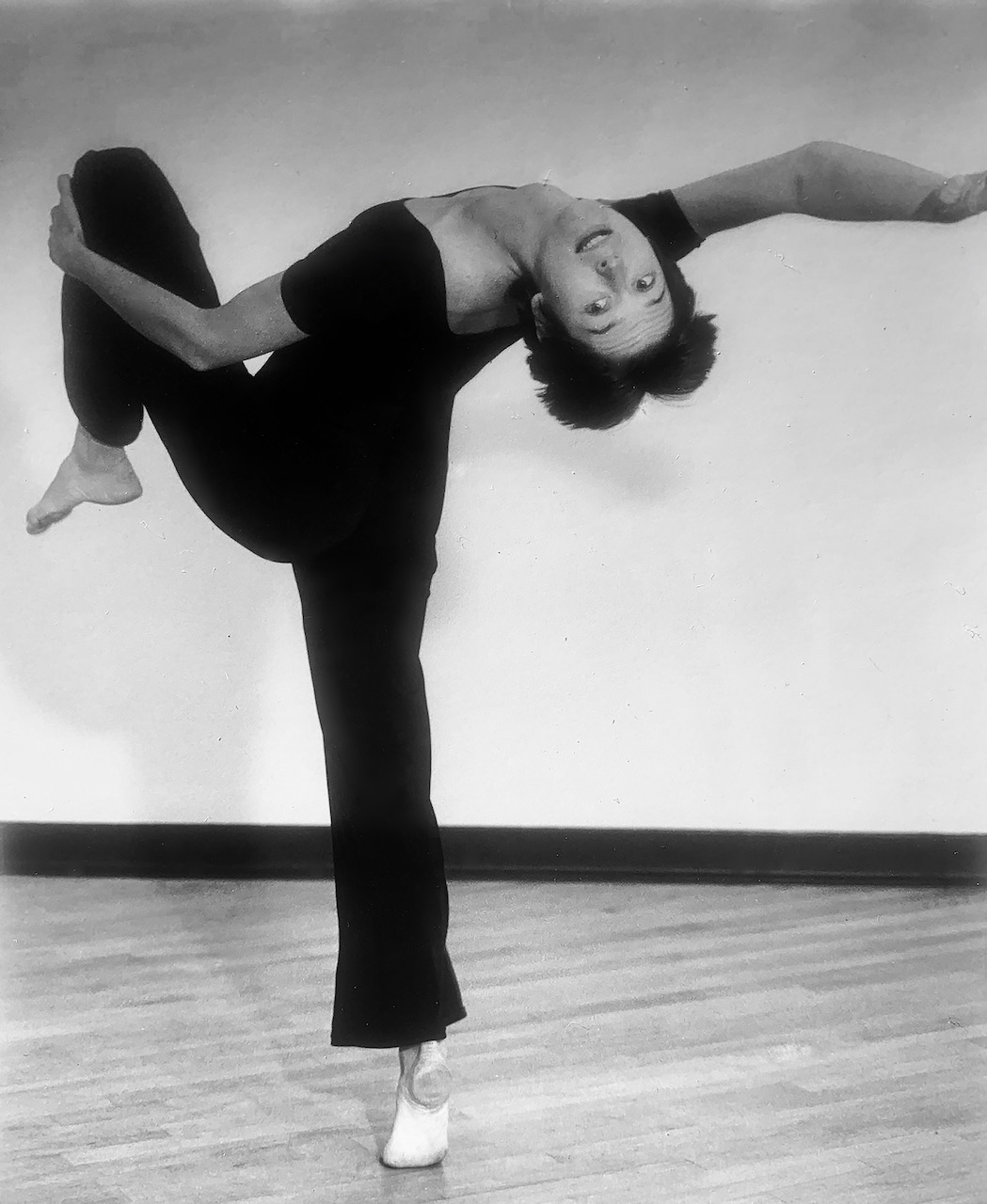

Blurred Genres, opening solo — 9’.53’’

Susan Foster dancing in the opening solo of her piece Blurred Genres that was premiered at the Cunningham Studio in New York City in 1986:

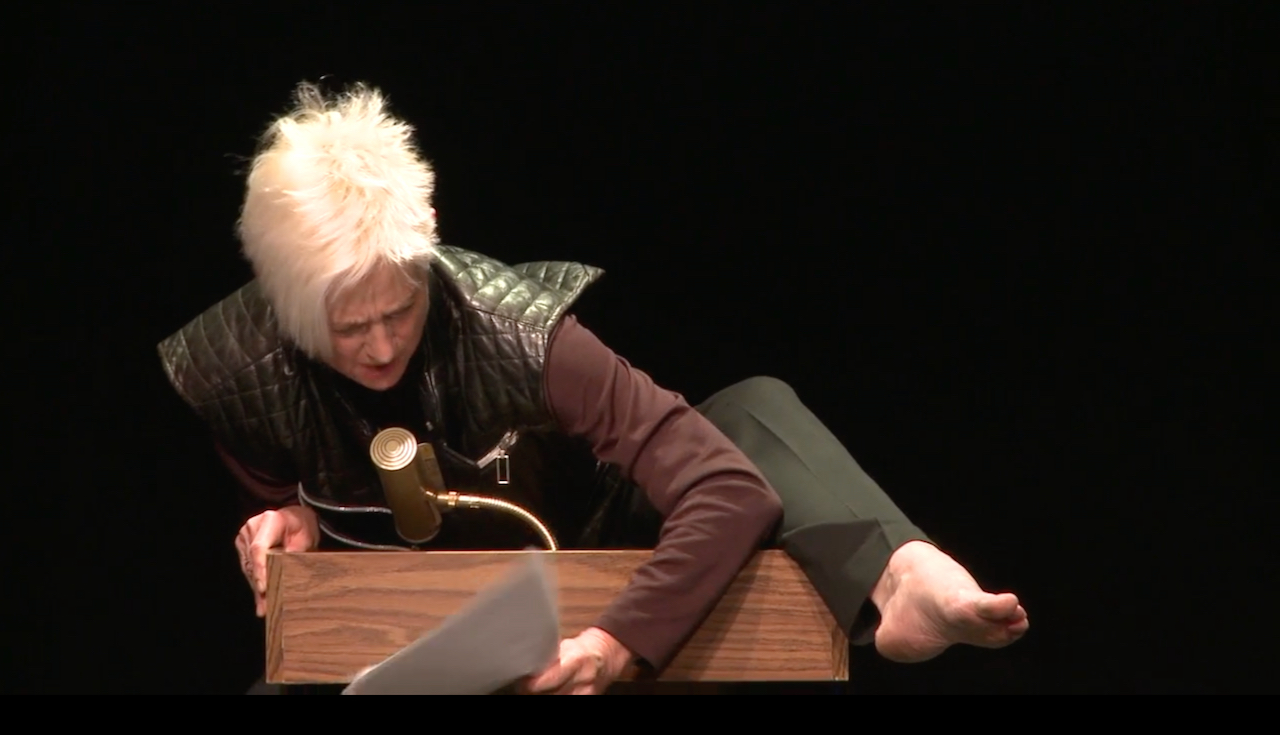

UCLA, 129th Faculty Research Lecture – March 23rd, 2021

Susan Leigh Foster, Distinguished Professor, World Arts Cultures and Dance:

What Dancing Does 38’.12’’

0.’ introduction by the Academic Senate Chair

1.’27’’ introduction by Emily Carter

4’.58’’ Susan Foster – introduction

7’.10’’ Four Perspectives on What Dancing Does

7’.44’’ Dancing as Thinking

15’.11’’ Dancing as Signifying

23’.04’’ Dancing as Coercion and as Survival

28’.53’’ Dancing as a Form of Exchanging

35’.43’’ Susan Foster – conclusion

Works in Progress / Podcast of the UCLA School of the Arts & Architecture – Susan Leigh Foster: How dance functions in our lives 23’.58’’ – April 2021

Performance Research 25.6/7 : pp.186-189 – 2021

Susan Leigh Foster: Guts ’n’ Brains, building relationality in dancing

Three Performed Lectures – March 2011

Choreographies of Writing